Milk Quality

A cow’s diet and contentment affects both the taste and nutritional value of the milk she produces, as well as her overall health and her impact on the land.

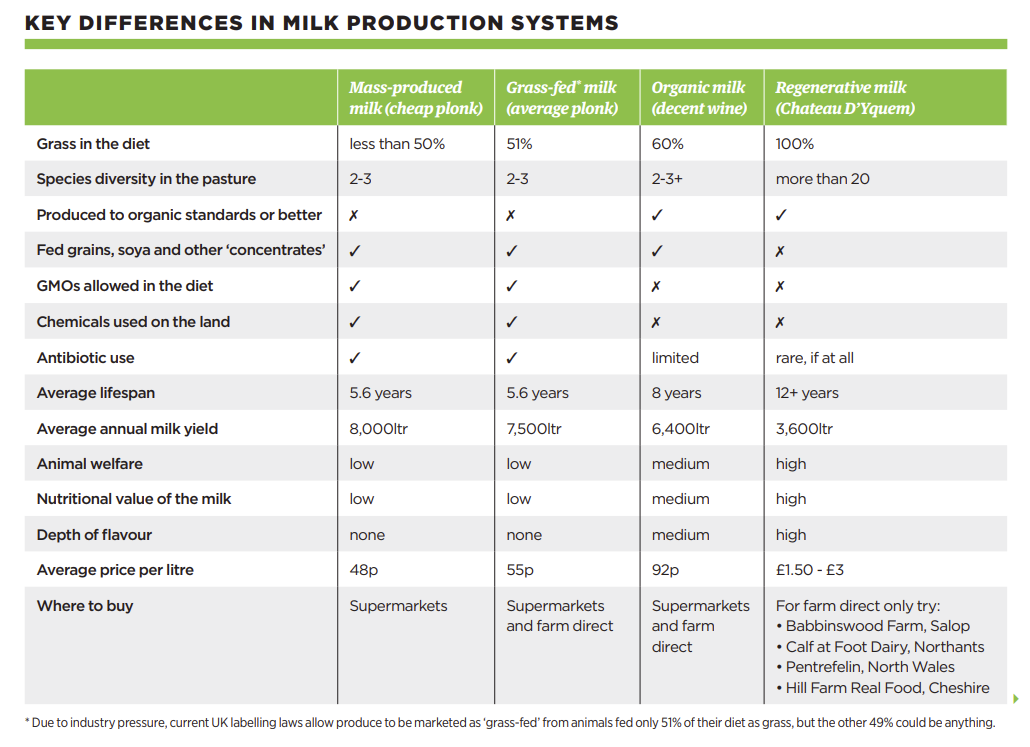

The increasing industrialisation of milk over the past 40 years has led to an almost tasteless product of bland uniformity, like mass-produced wine. As with most things in food and farming, a focus on profit by way of increasing production volumes for the cheapest cost has driven a significant decline in quality. In the case of milk, this means the quality of the product as well as the quality of the life of the cows.

Those fortunate enough to grow up in the 1960s or before will likely remember milk as something with body and a depth of colour and flavour. It altered with the seasons as the cows’ diet changed from the sweetness of lush spring grass, to the fragrance of summer meadows, to the minerally depths of conserved winter fodder. A glass of milk was a meal to be savoured, and you had to be first to the fridge in the morning if you wanted the cream on your porridge.

Bas de Groot, a milk sommelier, travels the world tasting milk and teaches of its rich diversity and how the colour, flavour, aroma and body are as connected to the land and soil below the pastures on which the cows graze as is wine from a particular vineyard, giving milk from each farm and landscape a unique terroir.

For those who have only drunk cheap plonk, this might be a stretch of the imagination, but for those who remember the rich complexity of seasonal milk from cows outside grazing diverse native pastures, this will be fully appreciated.

FROM TONGUE TO TEAT

At its most basic level, milk is simply water that has been metabolised through the body of a cow with nutrients procured on the production journey from tongue to teat. That journey starts with the cow selecting what to eat and then that plant material being broken down and fermented in her rumen. The nutrients from the fermentation by-products are absorbed into the bloodstream and provide the building blocks for the synthesis of milk in the udder.

Milk production, however, places a significant metabolic demand on a cow, with around 500ltr of blood needed to flow through the udder to produce 1ltr of milk. The quality of the milk is governed by the quality and quantity of the nutrients in the blood and the ratio of utilisation between milk production and the cow’s own body maintenance.

As the size of the fermentation tank, the rumen, dictates the quantity of food digested, conventional dairies feed their cows ‘concentrates’, literally concentrated food in the form of cereals (grain), soya, palm kernel, brewers’ grains, brassicas, root crops and other feedstocks with the aim of increasing production volumes for every production unit (cow). Even silage (pickled grass) is a form of concentrate as, being partly pre-fermented, it passes more rapidly through the rumen and allows more to be consumed and yields to be increased.

THE PROBLEMS

The problem with all of these concentrates, however, is that they are not what cows are designed to eat and consequently they severely impact the rumen microbial community to the detriment of the cow’s health and milk quality.

The reason is two-fold:

Feeding concentrates lowers rumen pH and this can lead to serious health problems and even death if the pH goes too low.

The by-products from the microbial breakdown of concentrates are completely different to those from a cow’s natural diet of pasture and this changes the nutrient availability and thus the components in milk.

To counter the negative health effects of the yieldboosting concentrates, conventional dairies must also feed buffering minerals.

However, these have their own impact as every cow’s needs are unique and constantly changing. Thus cows must continuously divert energy and nutrients from other bodily functions to maintain rumen homeostasis.

This increased metabolic stress can be understood when we consider the basic energy production system within the mitochondria of all cells — the Krebs cycle. Interconversions of Krebs cycle intermediates are controlled by enzymes that require vitamin-derived cofactors and minerals to function. These vitamins and minerals diverted to support energy production for rumen maintenance and high milk yields mean that there are less for body maintenance and less in the milk.

AN EARLY GRAVE

The demands placed on the modern high-production dairy cow mean that her life is short and compromised. The youthful vitality she had when she entered the herd at calving when two years old soon ebbs away.

The average yield of a UK dairy cow, according to data from National Milk Records, is 28.6ltr per day, while the average number of lactations is just 3.6. This means that cows are culled (euphemistically called ‘leaving the herd’) on average at 5.6 years old.

By comparison, a cow raised in a regenerative system, producing lower volumes of high-quality regenerative milk and fed a natural diet consisting solely of diverse pastures with access to browse hedgerows and trees and no dysbiosis-causing concentrates, doesn’t have the same metabolic stresses, doesn’t need to continuously buffer her rumen pH and can be productive and stay healthy well into her teenage years. A healthy cow’s lifespan can be 20 years.

Furthermore, the more concentrates fed, the less grass is consumed, and yet pasture provides the most accessible source of a full range of vitamins and minerals in a balanced ratio. And the more species diversity in the pasture and the healthier the soil, the wider the range and availability of micronutrients in the pasture for the cows to select.

While different diets affect all aspects of milk components, the most significant impact is in the amount and quality of the milk fats and the micro-nutrients.

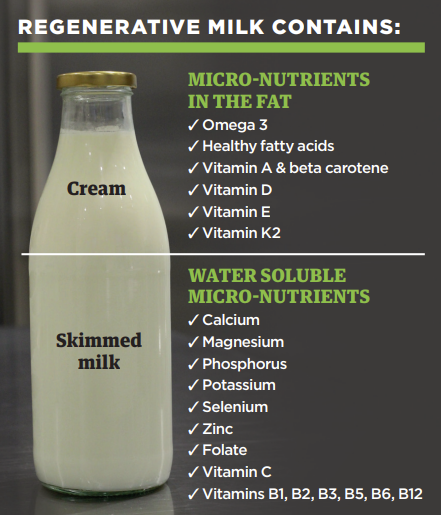

Milk fat contains triglycerides, diglycerides, fatty acids, sterols and carotenoids, as well as the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E and K. The four main fatty acids in milk are myristic, palmitic, stearic and oleic acids, found in abundance in coconut oil, palm oil, soy oil and olive oil respectively. Oleic acid, being liquid at room temperature, gives a ‘softer’ milk fat and consequently butter more easily spread from the fridge.

HEALTHY FATS

Cows grazing on diverse pastures will produce milk fats containing high quantities of oleic acid, as well as more carotenoids, giving the milk a creamier colour, more vitamin D from being out in the sun and more vitamin K2, both essential for calcium metabolism, and they will also produce milk containing omega-3 fatty acids.

Cows fed grain, even in small quantities (due to its effect on the rumen microbial community), however, produce more stearic acid, giving harder butter, less vitamin D and K2 and no omega-3 because the larger quantity of omega-6 from the grain displaces the omega-3. Often industrially produced milk has to have vitamin D added because the cows don’t spend enough time out in the sunshine and consequently both the cows and the milk they produce are deficient in this vital nutrient.

THE TERROIR OF REGENERATIVE MILK

Water-soluble vitamins C, B1, B2, B5, B6, B12 and the minerals calcium, magnesium, phosphorous, potassium, selenium, zinc and folate are all found in regenerative milk from cows grazing diverse pastures on healthy soils. The diversity of plant species, including herbs and hedgerows, is what adds depth and complexity of flavour. This is where the terroir of the farm can be detected in regenerative milk.

However, if these same cows were to graze mono-culture ryegrass pastures, or a duo-culture of ryegrass and clover soaked in artificial nitrogen fertilisers to force bulk growth, as is ubiquitous in the conventional dairy industry, they would not obtain all the micronutrients they need as both the pasture and the soil will lack the diversity of plant and microbial species to provide the necessary nutritional building blocks.

Additionally, the nutrients they do get are likely diverted to rumen maintenance and additional energy production as noted earlier.

The B vitamins in particular can quickly be used up as enzymatic cofactors in the Krebs cycle. All this means that milk from these cows is bland, flavourless and nutritionally deficient as has been evidenced by many research studies, notably by Newcastle University, looking at diet and milk quality.

The diet of the cow, the quality of her milk and the quality of her life are inextricably linked. The regenerative milk equivalent of Chateau D’Yquem can only come from healthy, vibrant cows which spend their days lazily grazing diverse pastures growing in healthy soils.